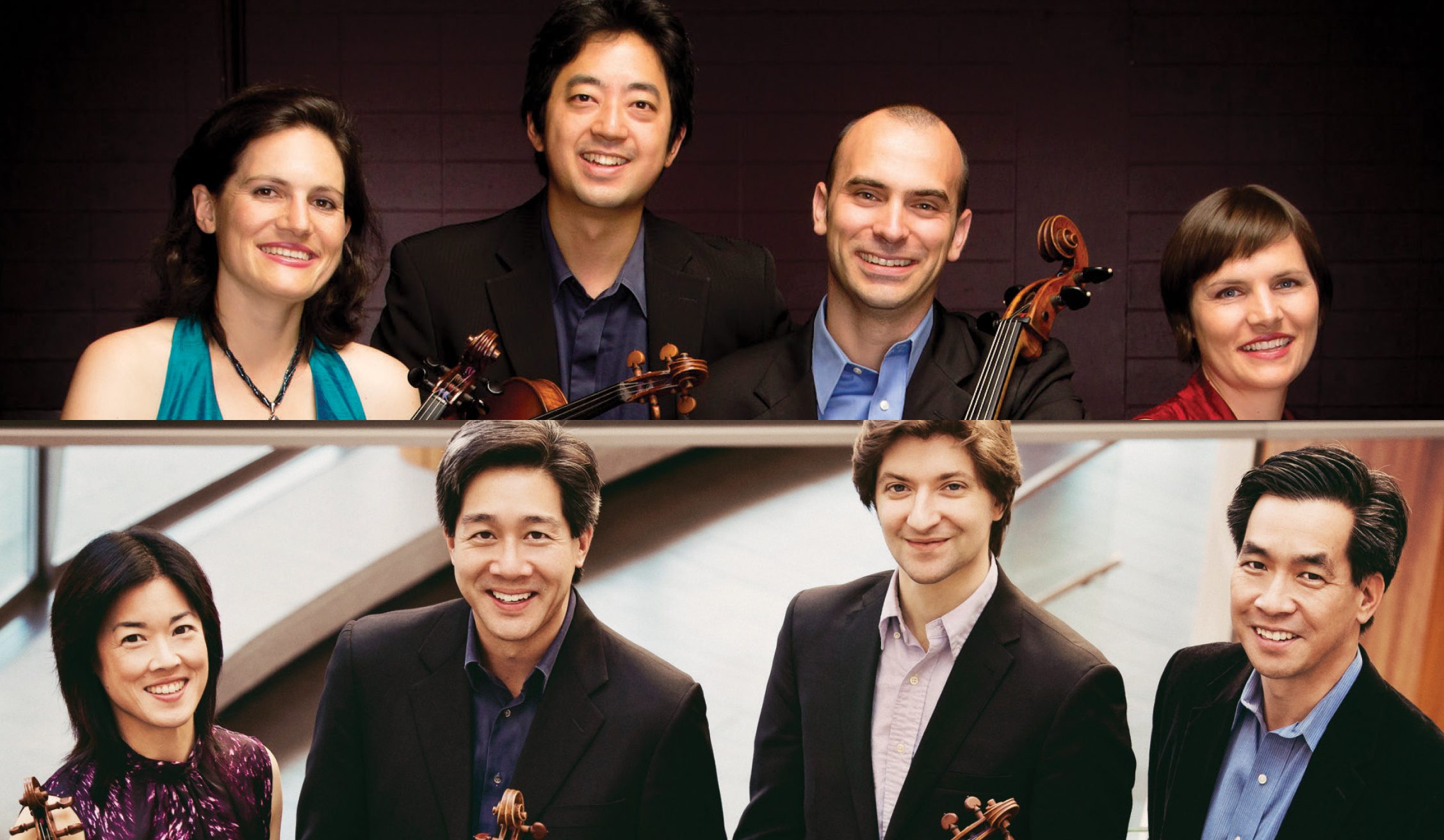

Jupiter & Ying Quartets: July 17, 2017

Musicians from two of the Festival’s resident quartets join forces for an evening of lush Viennese masterpieces. Mozart’s String Quintet, scored for two violas, exposes a dense texture of inner voices and some of Mozart’s most dark, impassioned chamber music writing. On the second half, Schoenberg’s Verklärte Nacht (Transfigured Night), is performed in its original scoring for sextet, which highlights the work’s unceasing harmonic tension, alternatingly sumptuous and breathless.

WOLFGANG AMADEUS MOZART

String Quintet No. 4 in G Minor, K. 516

The year 1787 was difficult for Mozart in several ways. Although he had arrived to Vienna in 1781, Mozart still struggled to find the steady and fulfilling position he sought within the city’s musical world. He had a few years of lucrative success as a composer-performer, premiering several piano concertos each season; however in 1786-1787, he turned his attention to operatic collaborations, resulting in a sharp decline in income that could not adequately sustain his lavish lifestyle. Moreover, in April of 1787, Mozart learned that his father’s health had significantly worsened, which caused particular anguish as the younger Mozart was unable to take the time to visit Leopold in Salzburg.

These trying circumstances surrounded Mozart’s composition of two String Quintets, K. 515/516, often considered the summit of his chamber music writing. Observing the sharp contrasts between the two quintets, commentators frequently draw a comparison between these and Mozart’s Symphonies No. 40 and 41, composed the following year – a comparison bolstered by the respective key signatures of each pair (C Major and G minor). The dark tone of this quintet is enhanced by Mozart’s choice of ensemble, a string quartet plus an additional viola. This dense instrumentation was nonstandard; and although, by force of these quintets, Mozart was the composer to popularize the genre, he was not without predecessors. Mozart was likely inspired by Michael Haydn (younger brother of Joseph), an old acquaintance from Salzburg who had published his own viola quintets over the preceding decades.

Mozart’s father died twelve days after Mozart completed the String Quintet No. 4. Mozart managed, despite his sorrow, to complete Don Giovanni later the same year, which received a spectacular premiere in Prague. And by the end of the year, Mozart at last obtained part-time royal patronage as “chamber composer” to Emperor Joseph II. It was not as grand of a post as Mozart may have hoped for, but it proved sufficient incentive for Mozart to remain in Vienna.

ARNOLD SCHÖNBERG

Verklärte Nacht (Transfigured Night), Op. 4

Schönberg was twenty-five when he composed Verklärte Nacht, considered an epitome of the Austro-German late Romantic idiom that characterizes Schönberg’s early compositions. The idiom is built upon a self-conscious maximization of the formal and harmonic styles of Brahms and Wagner; consequently, the resulting music features dense and contrapuntal chromaticism, motivic development and manipulation, and prolonged periods of breathless tension.

In light of Schönberg’s future developments, it may be tempting to read Verklärte Nacht as a pivotal moment, a farewell to the lush tonality of the nineteenth century before Schönberg’s expressionist and serial turns. However, it was not received, or conceived, in that way. For one, audiences initially reacted hostilely to its premiere in 1902: the harmonic language was still challenging, and it was perceived as too dramatic and complex for intimate chamber music. Nevertheless, Schönberg stayed his course, pursuing the same compositional paths in the same maximalist spirit throughout his career. Reflecting on Verklärte Nacht in 1937, Schönberg remarked: “Nobody has heard it as often as I have heard this complaint: ‘If only he had continued to compose in this style!’ The answer I give is perhaps surprising. I said: ‘I have not discontinued composing in the same style and in the same way as at the very beginning. The difference is only that I do it better now than before; it is more concentrated, more mature.’” Indeed, Schönberg saw not a break but a continuity between the counterpoint, texture, and development of Verklärte Nacht and the techniques of his later works.

The title of Verklärte Nacht came to Schönberg from a poem by Richard Dehmel (1863-1920), published in his 1896 collection Weib und Welt (Women and the World) and reproduced in translation below. Despite the work’s poetic inspiration, Schönberg did not consider it “program music” in the traditional sense, in that it does not portray action or drama, but rather is “limited to drawing nature and expressing human feelings.” Dehmel himself, having been present for the premiere, conveyed his impression to Schönberg: “I had intended to follow the motives of my text in your composition, but soon forgot to do so, I was so enthralled by the music.”

Transfigured Night

Two figures pass through the bare, cold grove;

the moon accompanies them, they gaze into it.

The moon races above some tall oaks;

No trace of a cloud filters the sky’s light,

into which the dark treetops stretch.

A female voice speaks:

I am carrying a child, and not yours;

I walk in sin beside you.

I have deeply sinned against myself.

I no longer believed in happiness

And yet was full of longing

For a life with meaning, for the joy

And duty of maternity; so I dared

And, quaking, let my sex

Be taken by a stranger,

And was blessed by it.

Now life has taken its revenge,

For now I have met you, yes you.

She takes an awkward step.

She looks up: the moon races alongside her.

Her dark glance is saturated with light.

A male voice speaks:

Let the child you have conceived

Be no trouble to your soul.

How brilliantly the universe shines!

It casts a luminosity on everything;

you float with me upon a cold sea,

but a peculiar warmth glimmers

from you to me, and then from me to you.

Thus is transfigured the child of another man;

You will bear it for me, as my own;

You have brought your luminosity to me,

You have made me a child myself.

He clasps her round her strong hips.

Their kisses mingle breath in the night air.

Two humans pass through the high, clear night.

Translation: Scott Horton.