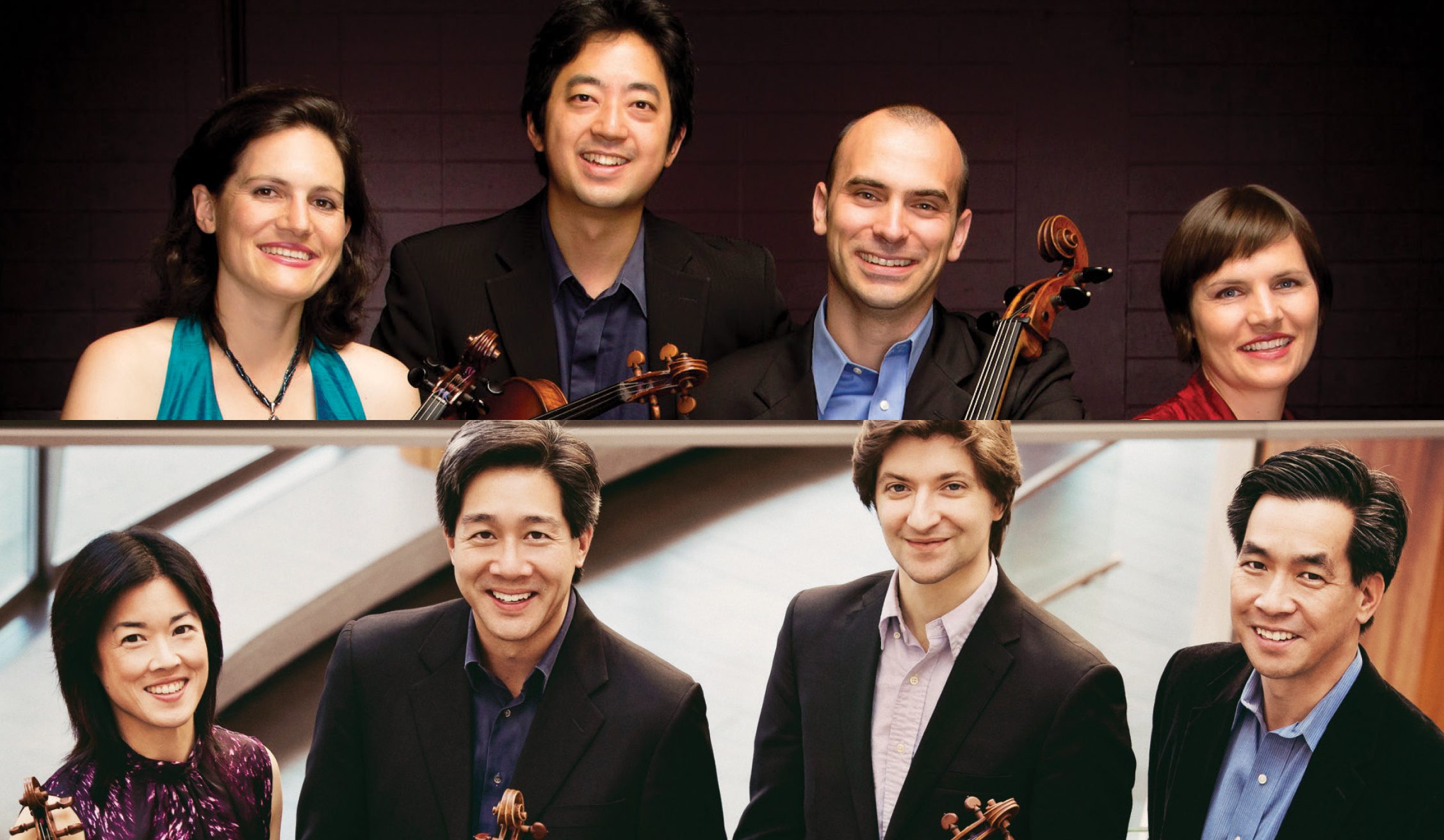

Jupiter & Ying Quartets: July 22, 2019

The Jupiter String Quartet return to the Festival and join forces once again with the Ying Quartet for an evening of string music, starting with Dohnányi’s mature sextet, putting a lush coat on a distinctly Brahmsian genre, even in the 1930s. Shostakovich’s and Mendelssohn’s works, on the other hand, display both composers’ youthful voices – each was written before their twentieth birthday, yet both are already bursting with their authors’ unique voices.

This evening’s program offers glimpses at the early output of three precocious composers: each piece was written (at least in an initial version) before the composer reached the age of twenty.

ERNŐ DOHNÁNYI

String Sextet in B-flat Major

Born in Bratislava (then Austria-Hungary), Ernő Dohnányi became best known throughout his life as a central force in the musical life of Budapest, Hungary. He became director of the Budapest Philharmonic, and later also the national Academy of Music, where he devotedly organised hundreds of concerts each season. He was a formidable and prolific pianist, having studied with István Thomán, himself a student of Liszt; during one notable season, Dohnányi performed the complete piano works of Beethoven. He maintained his posts at the Philharmonic and the Academy until legislation was passed in the 1940s requiring that the institutions dismiss all of their Jewish personnel; Dohnányi chose to resign from both rather than carry out the discriminatory law. He left Europe after World War Two, settling first in Argentina and then Tallahassee, Florida, where he taught music at Florida State University until his death in 1960.

Dohnányi’s String Sextet takes us back to his youth in Bratislava, a city which he described in his memoirs as immensely musical. As a child, he received early music lessons from his father, and later from the local cathedral organist. He composed an initial version of this sextet at the age of 17, as he was preparing to submit a portfolio for admission to the Budapest Music Academy in 1893. Having gained admission, he began lessons with Janós Koessler; however he continued to return to the Sextet, refining the work over the coming years, and entering it into the royal competition, where it received an honorable mention. Even this did not satisfy Dohnányi, who continued to tweak the work until its full premiere, in its final version, in the composer’s hometown in 1900. From that point on, the work remained dormant, and it was only recently unearthed, and at last published, in 2005 through the work of Hungarian violist Péter Bársony.

DMITRI SHOSTAKOVICH

Two Pieces for String Octet, Op. 11

Long before he acquired his reputation as one of the twentieth-century’s most prodigious and successful string quartet composers, Shostakovich dabbled at something rather more elaborate – a suite for string octet, composed while he was still an eighteen-year-old student at the St. Petersburg Conservatory. The projected five movements were not completed, but the Prelude and Scherzo which were have traditionally been paired in performance.

The string octet is not an obvious form for a student composer. Stravinsky, whom Shostakovich admired deeply, had the previous year completed his own ambitious Octet– scored, however, for winds and brass, rather than the double-quartet instrumentation of Shostakovich’s. The more imposing precedent would have been the octet of Felix Mendelssohn. And yet, in composing his Scherzo, Shostakovich may have been gesturing to the work of both composers: Stravinsky had composed a smattering of Scherzos, including the Scherzo fantastiqueand Feyerverk(Fireworks) in his own relative youth; and Mendelssohn famously dashed off effervescent scherzos with apparent facility, including the third movement of his own octet.

Shostakovich’s inclination toward Stravinsky’s new directions was not shared by his composition teacher, Maximilian Steinberg. As Shostakovich wrote, Steinberg “made a sour face” upon reading the Scherzo, and “expressed the hope that, when I turn thirty, I will no longer write such wild music”. Even so, Shostakovich maintained confidence in his artistic direction. Writing about the Octet to his then-girlfriend, Tatiana Glivenko, he appeared to brim with pride: “I’m gradually becoming more of a modernist.”

FELIX MENDELSSOHN

String Quintet No. 1 in A Major, Op. 18

Immediately after composing the above-mentioned octet which inspired Shostakovich, Mendelssohn wrote his first string quintet, at the age of seventeen. In his own choice of ensemble, Mendelssohn in turn took inspiration from Mozart, who, late in his life, intensified the string quartet texture with the addition of a second viola. At the time, young Mendelssohn was working as an apprentice, churning out – and performing – music in all conceivable genres – symphonic, chamber, solo, concerto, and operatic – at a staggering pace. Many of these works were composed in view of the fortnightly “musicales” – fashionable concerts held in the Mendelssohn family’s dining room at their Berlin mansion on alternate Sunday mornings – where musicians, intellectuals, and other elite members of society gathered. Felix was typically found on the conductor’s podium, or else at the keyboard alongside his sister Fanny.

Another frequent musical participant at the musicaleswas the violinist Eduard Rietz. Only a few years Mendelssohn’s senior, Rietz had already been made leader of the court orchestra in Berlin. Although he was engaged as Mendelssohn’s violin teacher, the two were in fact close friends, and Rietz joined Mendelssohn in playing this newly composed string quintet in 1826. It was Rietz that Mendelssohn had in mind when composing the first violinist’s part of the octet; and Rietz shared Mendelssohn’s then-uncommon fascination with Bach, assisting him in the revival performance of the St. Matthew Passion.

In 1830, Mendelssohn was struck by a great trauma upon learning, while on tour in Paris, of Rietz’s unexpected death from tuberculosis. He wrote home: “I can recall nothing without being reminded of him, that I shall never hear music, or write it, without thinking of him.” The fact that Mendelssohn heard the news on his twenty-third birthday only added to his grief: “I remembered how invariably on this day he arrived with some special gift which he had long thought of, and which was always as pleasing, and agreeable, and welcome as himself.” Mendelssohn coped with the loss by returning to the string quintet, and composing a new Intermezzo in Rietz’s memory to replace the original Minuet and Trio.